Letter 4: Simone de Beauvoir Against the "Girlie"

On "Feminine Energy" as a Social Construct, the Infantilisation of Womanhood and How Her Philosophy Can Help Us Live More Freely

Dear Reader, this is the free biweekly Earth Poet essay. To support this newsletter, please subscribe for free to begin, or go deeper as a paid reader to access weekly essays and the Dead Poet Advice column.

Much Love,

Earth Poet

Femininity as a Social Construct & Lifelong Performance

One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949)

In the last few years, hashtags like #GirlDinner, #GirlMath, and #HotGirlWalk have amassed billions of views on TikTok.

A new generation of young women is embracing hyper-feminine identities — celebrating softness, humor, and curated self-expression — often in a tongue-in-cheek manner.

Yet this is femininity not just as behavior, or even as identity — it is femininity as an aesthetic performance: a curated, emotionally resonant version of self, styled, shared, and made viral.

It’s identity transformed into content.

And while much of it is framed as irony or empowerment, it also, even in jest, reintroduces an old pattern: the infantilization of women by women themselves.

Simone de Beauvoir saw femininity not as a biological essence but as a social construct — something imposed rather than inherited.

What society defines as “feminine” is not innate, but shaped by culture, expectation, and upbringing.

She argued that women are not born feminine; they are taught to become so, shaped from girlhood to align with the ideals of a patriarchal world, in a lifelong performance that limits their freedom and potential.

She observed that girls are taught from an early age to view their bodies as objects to be admired rather than instruments for action.

While boys are encouraged to master the world through exploration and achievement, girls are conditioned to prioritize how they appear to others, leading to passivity and self-surveillance.

The New Stage for Performance

Today, that conditioning has evolved in ways de Beauvoir likely couldn’t have imagined.

Social media — especially TikTok — has become the perfect stage for this performance.

It rewards visibility, repetition, and aesthetic coherence — all the things traditional femininity has historically demanded.

Add in an obsession with longevity and not being allowed to age.

The algorithm favors the polished, the pleasing, the emotionally legible.

A girlie knows how to pose, how to caption, how to turn her personality into a palette.

Self-Surveillance Disguised as Self-Expression

A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself.

— John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972)

Women have been taught to internalize the gaze — to see themselves as objects first, selves second.

What looks like self-expression is often a form of self-surveillance: a constant curating of how one appears, rather than how one feels.

It turns attention inward, toward managing an image, rather than outward, toward engaging with the world.

A woman becomes more accustomed to being observed than to observing for herself.

The Infantilization of Womanhood

The woman who is perpetually a girl is infantilized by society: she is not permitted to grow up, to assume full responsibility.

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949)

When womanhood collapses into eternal girlhood, we lose not just complexity — we lose autonomy.

The rise of infantilized aesthetics isn't as harmless as it perhaps appears.

It reflects a deeper fear: aging, fading, stepping out of the male gaze.

Essentially, women are being punished for aging — by society and by capitalism.

But what gets lost is the full expansion into adulthood — not adulthood as loss, but adulthood as freedom.

A Way Forward

Understanding how the performance began is only the first step.

The harder task is choosing, again and again, how to live beyond it — to refuse the roles that were written for us, even when they are offered back in new, glittering forms.

Freedom, Simone de Beauvoir reminds us, is not something given; it is something built, often in silence, often against the grain.

And it begins with the slow, stubborn work of reclaiming how we see ourselves, how we move through the world, and how we choose to be.

Three Steps to True Freedom

While today's girlie culture frames curated femininity as playful or empowering, Simone de Beauvoir would likely have seen it as another version of self-limitation.

Freedom, she believed, requires much more than reclaiming aesthetic roles.

It demands a deeper, harder kind of liberation — one that remains urgent even today.

Here are the three steps her thinking offers us toward true freedom:

1. Claim Existential Freedom

To emancipate woman is to refuse to confine her to the relations she bears to man, not to deny them to her.

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949)

De Beauvoir argued that women must stop seeing themselves as objects defined by others, and instead recognize themselves as full, free human beings — capable of action, choice, and transcendence.

Freedom begins by refusing to internalize the gaze and choosing to live for oneself, not for appearance or approval.

→ Claiming existential freedom today means refusing to live as a curated object.

It begins by recognizing that online spaces are designed to reward performance — and then consciously choosing when, where, and how to engage.

It might mean creating on your own terms, building spaces that prioritize dialogue over display, or choosing slowness and privacy in a system obsessed with speed and visibility.

Freedom may not mean rejecting capitalism entirely — but it demands resisting the pressure to package your selfhood as another marketable product.

It asks you to live not as a curated object, but as a subject: choosing creation over curation, presence over performance, and depth over display.

2. Achieve Economic and Social Independence

Her liberation depends on the abolition of her economic dependence.

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949)

Without material independence, women remain trapped — performing roles not because they choose to, but because survival demands it.

Today, capitalism demands constant visibility, self-branding, and emotional labor from women.

Without autonomy, the curated self becomes not just preferable but necessary.

Those who conform to aestheticized, emotionally accessible versions of femininity — softness, relatability, desirability — are often materially rewarded: more visibility, more opportunities, more social capital.

But these rewards only tighten the trap.

They bind survival and success to the performance of traits historically demanded by a patriarchal system — masking dependency as empowerment and limiting the paths women can take toward genuine freedom.

→ Achieving true independence today means building small, resilient ecosystems — creative communities, cooperatives, freelance work — where survival is rooted in autonomy, not spectacle.

It means resisting the structures that equate worth with marketability, and choosing forms of work, life, and creativity that prioritize freedom over visibility.

3. Reject Mythic Femininity

Man is defined as a human being and a woman as a female — whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949)

De Beauvoir warned against the cultural myths that idealize women as passive, pure, self-sacrificing, or eternally young.

Freedom, she argued, means rejecting these myths — refusing to accept fixed, aestheticized ideas of what it means to be a woman, and instead embracing the full, complex reality of being human.

Yet these same myths are resurfacing on social media today, repackaged as aspirational trends.

The rise of "feminine energy" coaching — urging women to become softer, more submissive, more nurturing to attract abundance or love — cloaks old expectations in the language of empowerment.

It suggests that femininity is an innate essence women have lost and must recover, rather than a role they were historically conditioned to perform.

The myth of eternal girlhood — passive, pure, emotionally legible — persists under new names: the clean girl, the sad girlie, the woman fully "in her feminine energy."

Social media trends promise empowerment through aesthetic conformity, but often end up reinforcing the same limitations they claim to resist.

But true freedom, as de Beauvoir insisted, lies not in performing idealized versions of womanhood — even beautiful ones — but in transcending them altogether.

→ Today, rejecting mythic femininity means resisting the pressure to package yourself into a consumable, emotionally legible brand — whether it’s the clean girl, the sad girlie, or the woman fully "in her feminine energy."

It means accepting the complexity, contradictions, and messiness of your real life, even when it doesn't translate into a coherent narrative for public consumption.

It means valuing subjectivity over spectacle — insisting that the life you live matters more than the image you project.

In Summary: Three Steps to True Freedom

Claim Existential Freedom: Refuse to internalize the gaze. Live for yourself, not for visibility or approval. Choose action, creation, and presence over self-surveillance.

Achieve Economic and Social Independence: Build your survival outside systems that demand constant performance. Seek work, communities, and creative paths that prioritize autonomy over marketability.

Reject Mythic Femininity: Resist the pressure to embody curated versions of womanhood — even beautiful ones. Embrace complexity, subjectivity, and the full, often messy reality of being human.

Freeing Yourself Toward a New Kind of Presence

The question, then, is not simply how we arrived at this point, but how we might imagine a way out — a way of freeing ourselves not through disappearance, but through a different mode of being altogether.

It will not be easy.

Social media exerts its pressures on everyone, and for women especially, it revives and amplifies ancient patterns: the imperative to be seen, to be pleasing, to be perpetually watchable.

John Berger understood that the first act of freedom must begin with sight: to recognize the gaze, to name it, and then to refuse to live under its constant surveillance.

Liberation, for him, was not about retreat, but about turning outward — looking at the world not as a mirror reflecting the self, but as a landscape full of life, detail, and meaning that exists whether we are seen or not.

To live freely now would mean shifting the axis of our attention: from self-monitoring to world-engagement; from managing appearances to cultivating presence; from curating emotion to inhabiting experience.

It would mean accepting the difficulty of this shift, the awkwardness, the invisibility it might entail.

It would mean risking not being legible in familiar ways — risking being misunderstood, overlooked, even forgotten — in exchange for something deeper, something less easily named.

Freedom today will not arrive as a sudden release, but as a practice: an accumulation of choices made quietly and stubbornly against the grain.

It will come not from perfect detachment, but from imperfect, human, often messy attempts to stay connected to life itself rather than to the endless reflections of it.

Presence, finally, is not an aesthetic.

It is a state of being in which you cease to watch yourself — and begin, again, to see.

Journal Prompt

Imagine yourself at your most free.

You are not being watched. You are not performing.

There is no mirror, no screen, no audience.

Just you — fully present, fully alive.

Where are you?

What are you doing with your body, your voice, your time?

What does your face look like when you're not trying to make it look like anything at all?

What do you notice when you're not noticing yourself?

Describe that moment.

Then ask yourself:

What small step could I take today to move closer to that freedom — even online?

Thank you for reading.

If this letter resonated, you can subscribe below for more.

And if you’d like to receive the Dead Poet Advice Column, where your questions are answered in the voice of someone long gone — that’s coming soon, too.

Much Love

— Earth Poet

Earth Poet is a weekly letter that unpacks quotes from cultural icons — writers, artists, provocateurs — and reflects on what they mean now. Each piece includes journal prompts and grounded takeaways. Free readers receive biweekly essays and midweek digests. Paid subscribers unlock weekly reflections and the monthly Dead Poet Advicecolumn — where voices from the past answer questions from the present.

References / Bibliography

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (1949), translated by H.M. Parshley, Vintage Books Edition, 1989.

Key ideas referenced: femininity as social construction, existential freedom, economic dependence, myth of the eternal feminine, subjectivity versus objectification.John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972), Penguin Books.

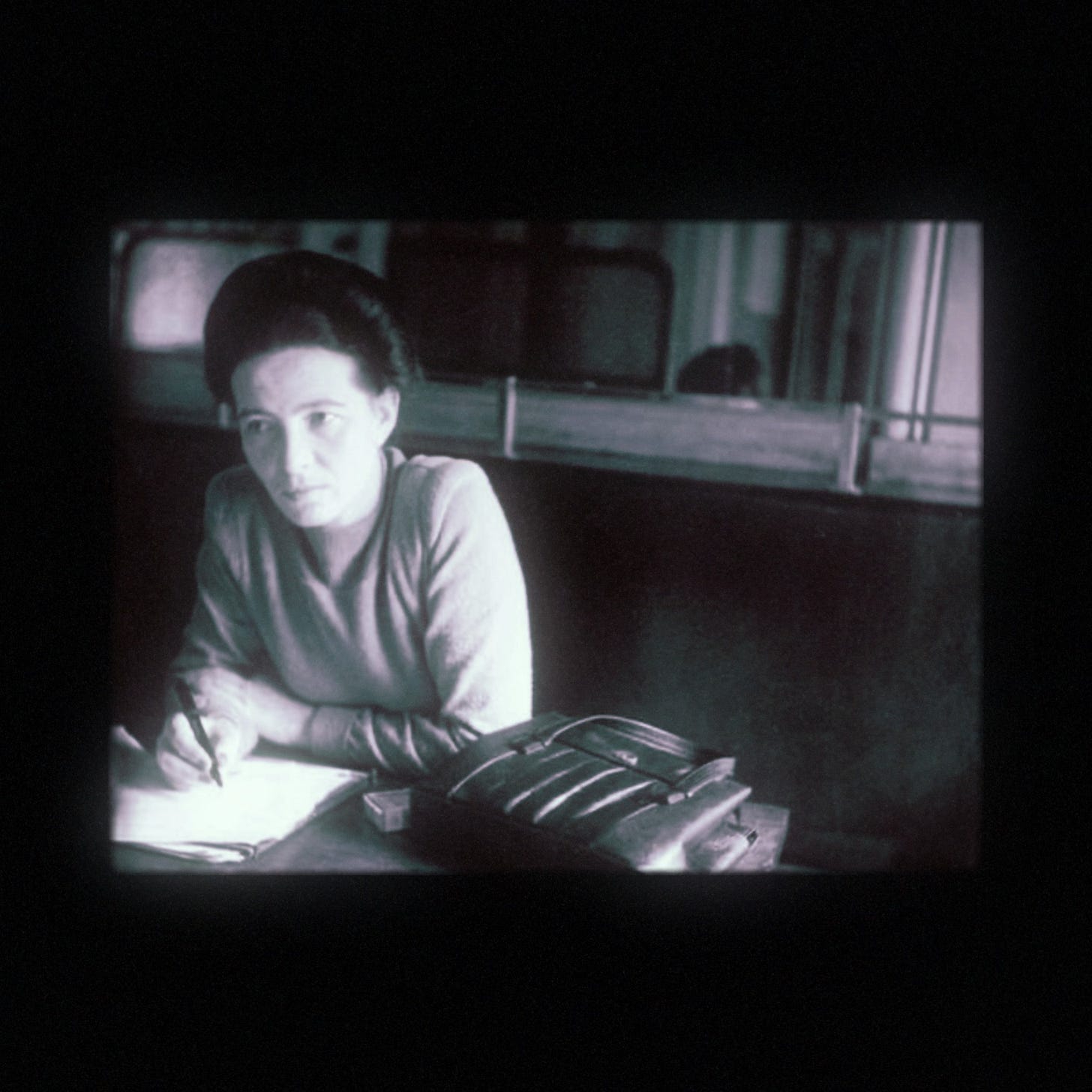

Key ideas referenced: the internalization of the gaze, women seeing themselves as objects first.Still from the 1970s documentary Simone de Beauvoir: Une femme actuelle.

© Respective copyright holders. Used here under fair use for educational and editorial purposes.TikTok Hashtags:

#GirlDinner, #GirlMath, #HotGirlWalk — referenced as examples of contemporary girlie culture and hyper-feminine social media trends (2022–2024 data observations).Contemporary Social Media Trends:

Observations on "feminine energy" coaching and content related to "hyper-feminine identity" circulating on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube circa 2022–2024.

beware of icons !

loved